on

Blog Post 2

This blog is part of a series related to Gov 1347: Election Analytics, a course at Harvard University taught by Professor Ryan D. Enos.

Introduction

This week in Election Analytics, we are talking about the economy. We are not the first to do this. It has long been theorized that the economy has an tremendous impact on election results, to the point that some predictors, like Yale professor Ray Fair, rely solely on economic variables in developing their models.

Based on this history of economic predictions, my primary question this week is to what extent the economy impacts midterm election outcomes and how effective economy-based predictions are. I have decided to focus specifically on whether the economic effect varies when looking at popular vote versus seat share and how this effect changes over time.

When choosing an economic independent variable, GDP (Gross Domestic Product, or the inputs and outputs of an economy) and RDI (Real Disposable Income) were two options. I decided to use RDI because I felt that it more accurately portrayed the economic situation of the voters themselves versus the larger movement of the economy as a whole. In their paper on voter behavior, Healy and Lenz, explore the influence of the economy on voters and ultimately find that, despite intending to base their vote on the incumbent’s entire term, voters only recall the most immediate economic past and the election-year economy influences their vote most. Based on this research, I decided to focus my analysis on the economic quarters immediately prior to the election.

Method

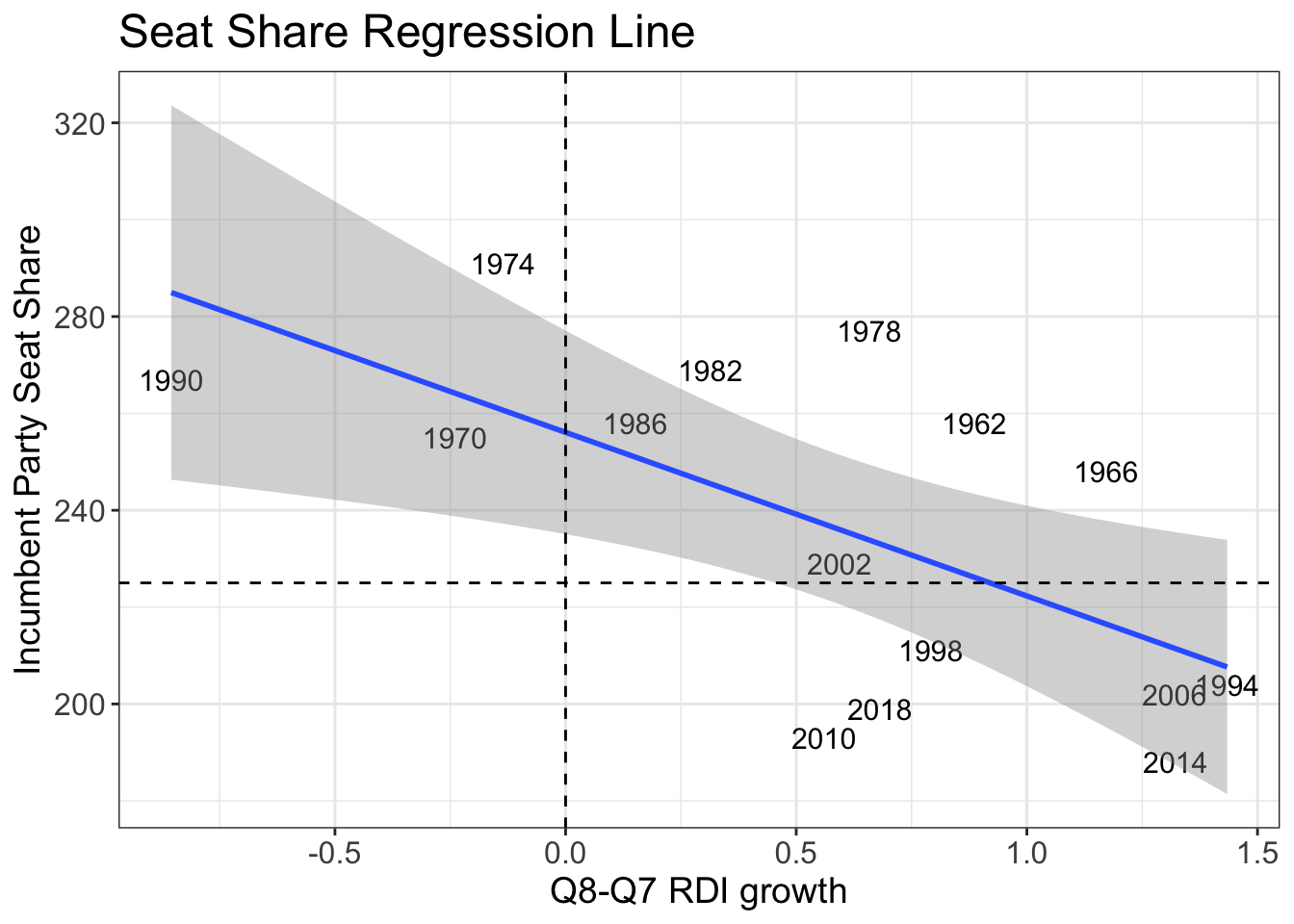

To begin my analysis, I coded scatterplots with vote share and seat share as dependent variables and RDI as the independent variable. I focused specifically on midterm election years. I fit regression lines to each model and finally ran tests to evaluate their quality.

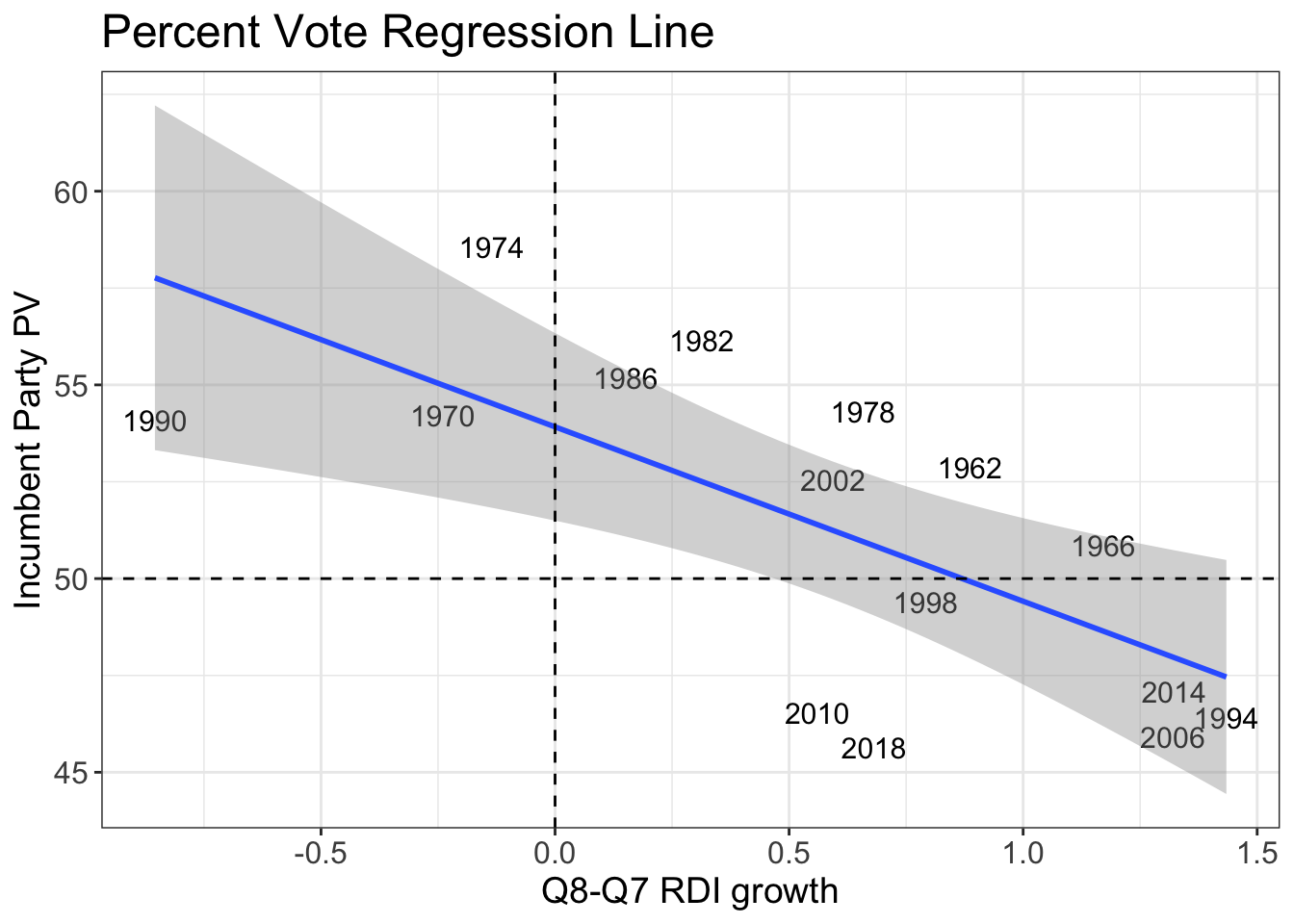

Popular Vote

This scatterplot at first glance seems to have a correlation. Most of the midterm values fall within the upper and lower bounds of the regression line on a negative tilt. The regression line of incumbent popular vote share and RDI yielded a correlation of -0.6874747 and an r-squared of 0.4726214. This is an mediocre correlation and a mediocre r-squared. It indicates that there is some correlation, but it isn’t necessarily strong enough to make accurate predictions.

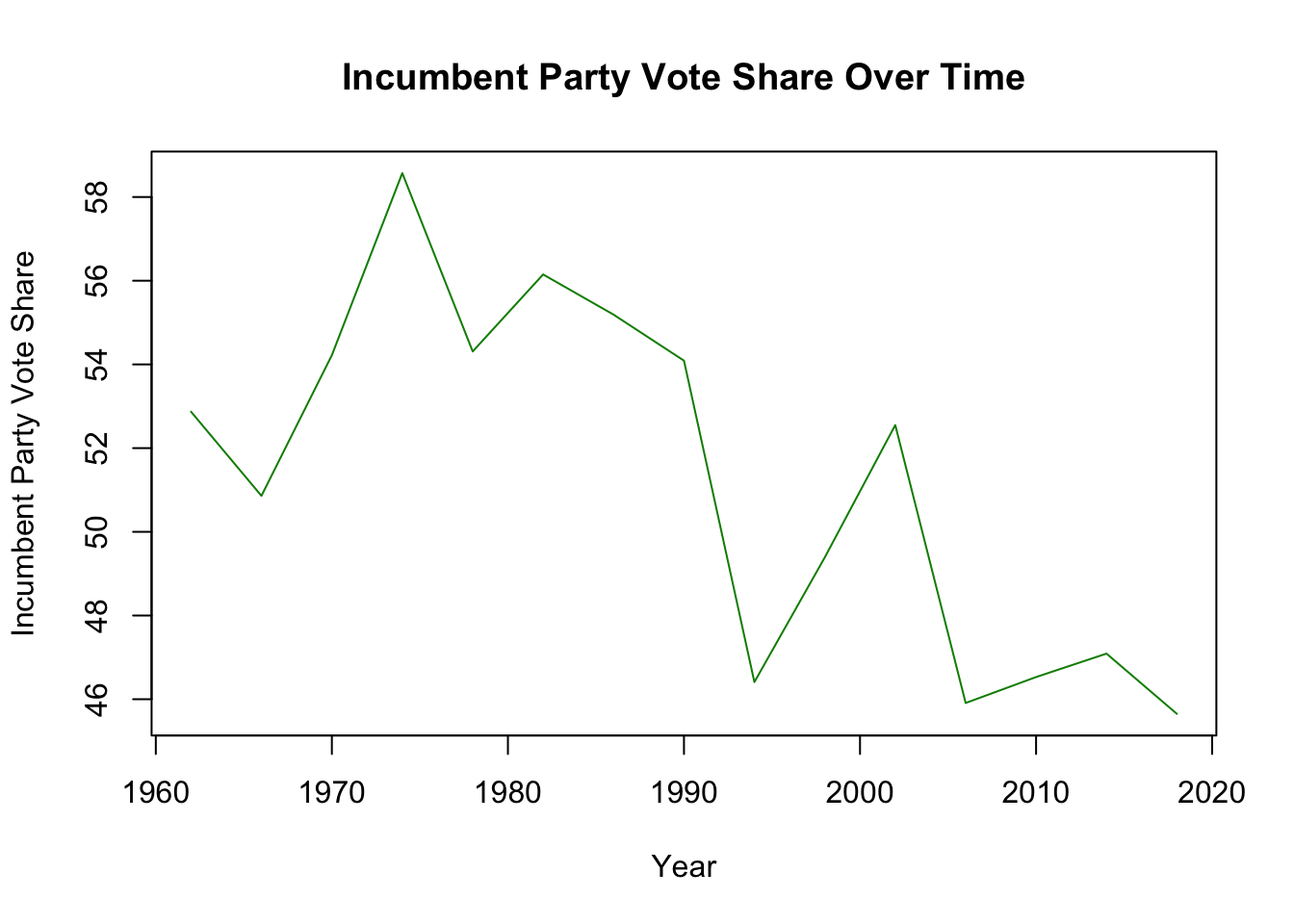

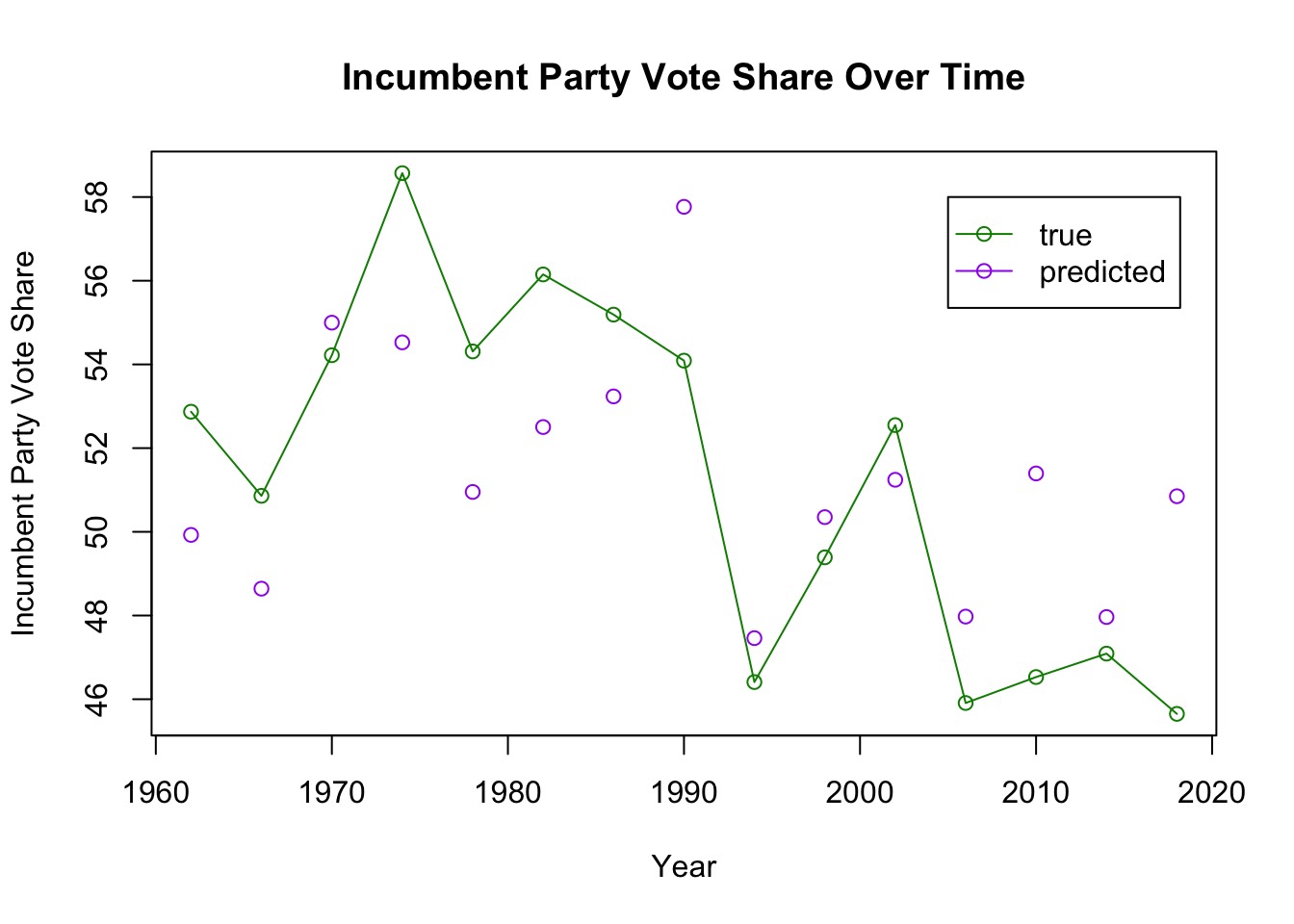

This graph plots the difference between the observed value and predicted value of party vote share and confirms our previous findings. Some of our predicted values, like 1970, 1994, 1998, and 2002, are close to the true value, but the majority are further away. The mean-squared error, a number summarizing the error, should be close to 1 in an accurate model. In this case, it is 2.965358, indicating once again that this model is mediocre.

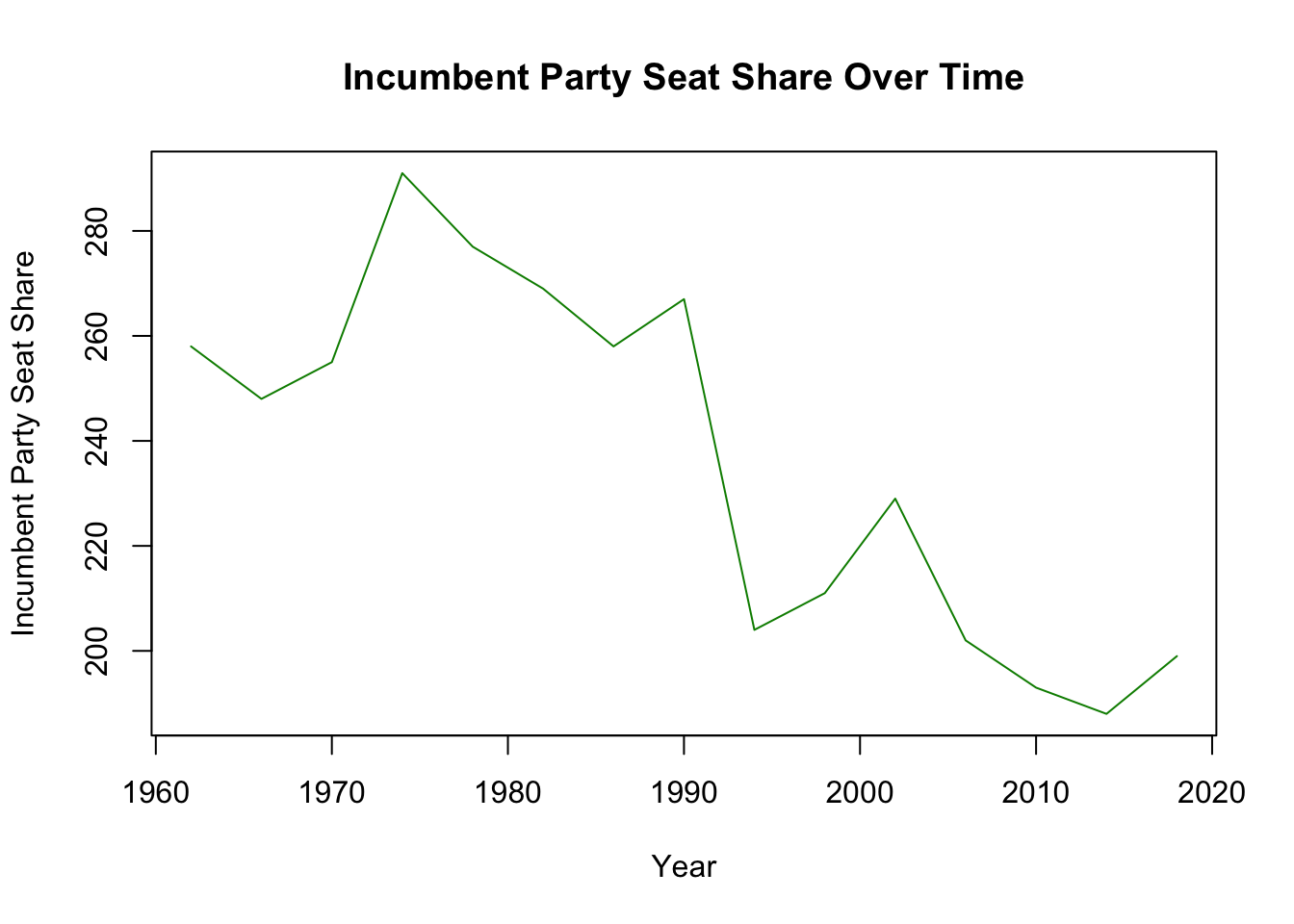

Now, let us turn to the seat share graphs.

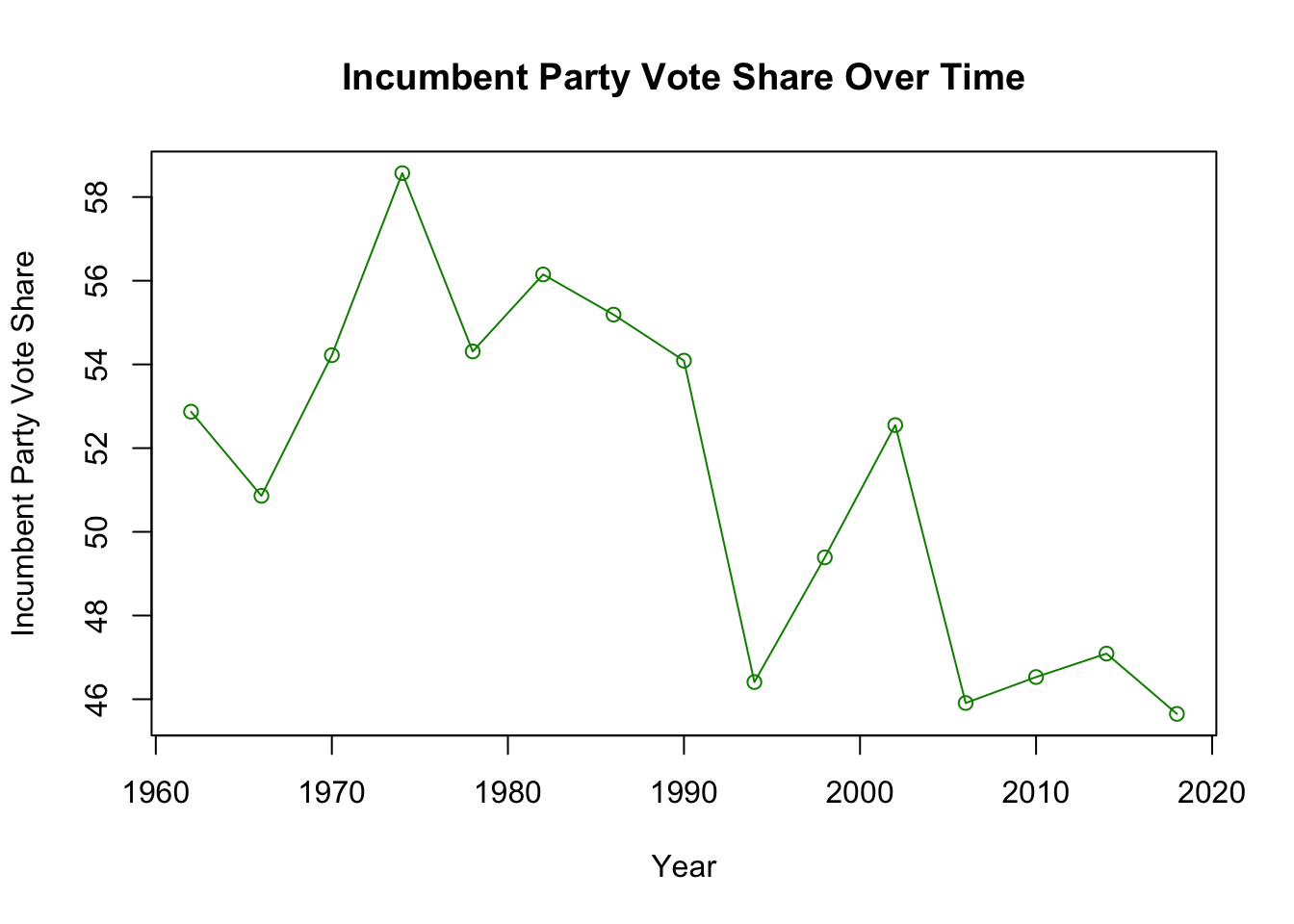

Seat Share

Compared to the Vote Share, the Seat Share graph seems to have less of a correlation. About half of the values fall within the upper and lower bounds, but half do not. This data has a correlation of -0.633019 and the regression has an r-squared of 0.4007131. Despite the visual dissimilarities, these values are actually quite similar, suggesting that there is little difference in economic correlation between popular vote and seat share.

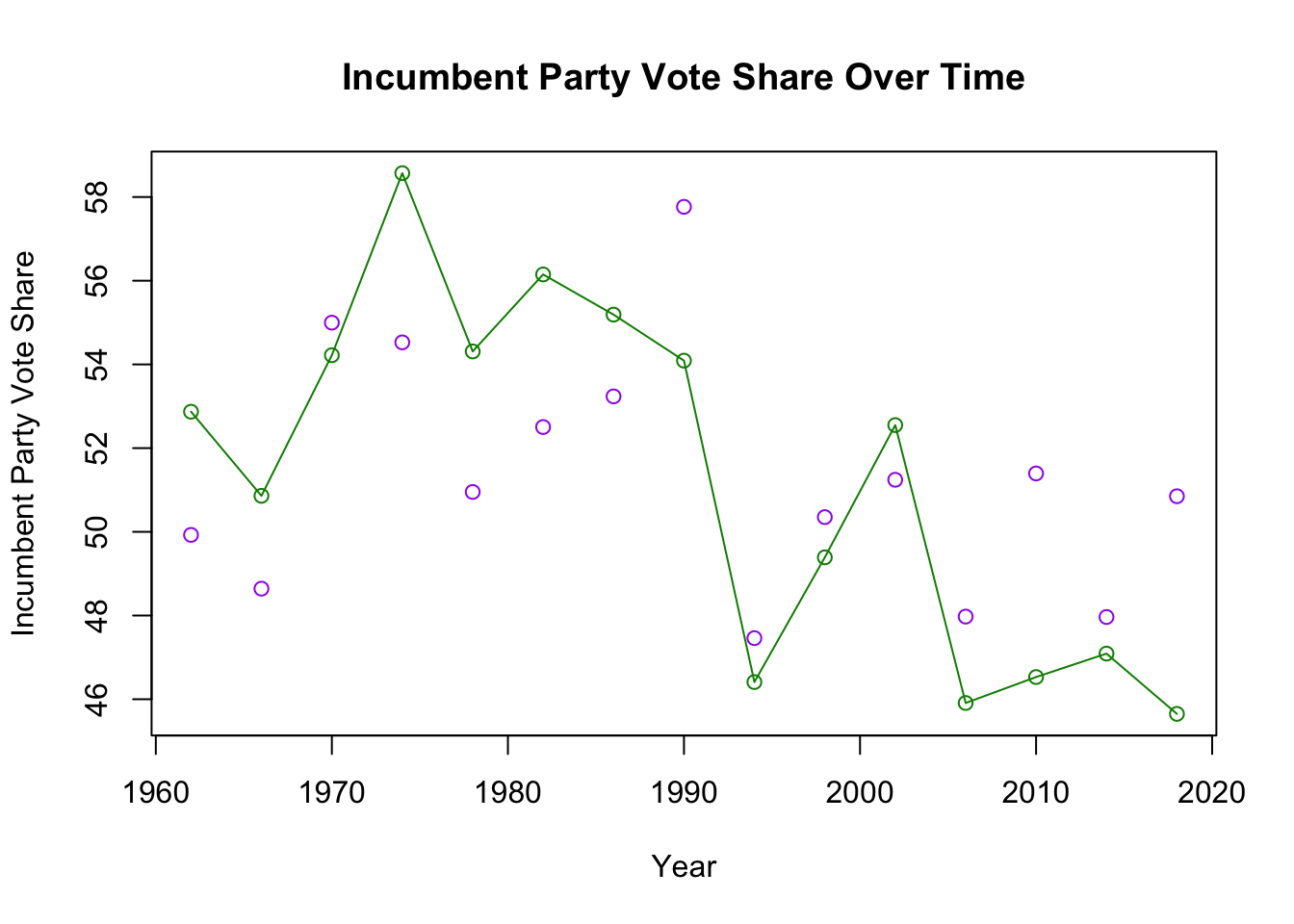

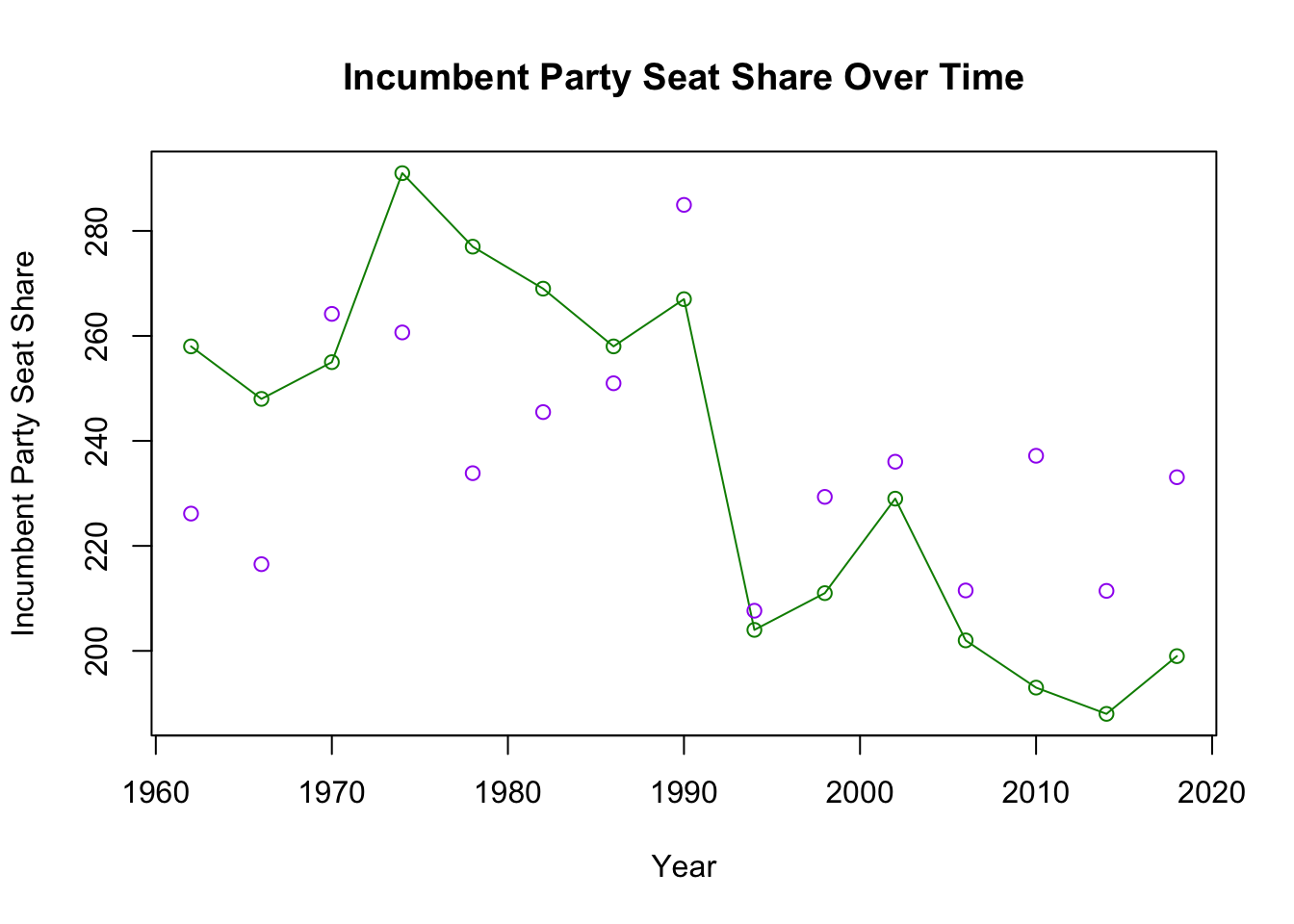

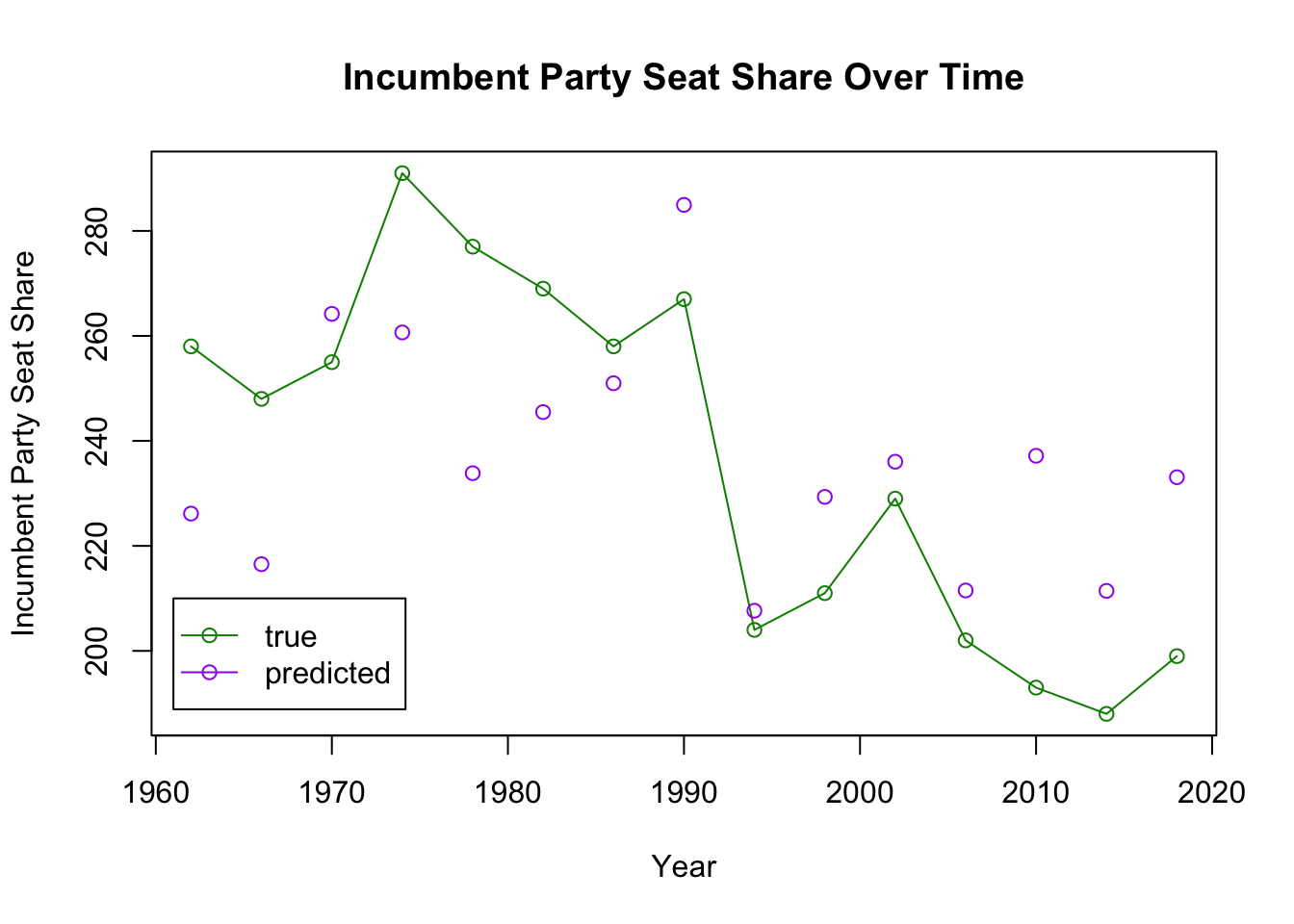

The plot between true and predicted value for seat share looks similar to the plot for popular vote, with predictions being largely inaccurate except for a few values. The mean-squared error in the case of seat share is drastically large at 25.75257, particularly compared to the case of vote share. The reasons for this are ripe for exploration in further posts.

Conclusion

There is some correlation between RDI and both vote share and seat share, however in both cases it is simply mediocre and not a good sole basis for prediction for midterm outcomes. The impact of the effect on popular vote versus seat share does not vary too much, however the MSE is drastically large for seat share, suggesting that vote share is a more reliable dependent variable. When investigating whether the predictive power of the economy changes over time, the answer is largely no. The incumbent party has lost vote share and seat share over time, indicating greater volatility in politics, but the inaccuracy of the predictions has remained. In the future, RDI could be a useful metric as long as it is combined with other factors, both economic and non economic.